The Pulitzer Prize Winner Who Couldn’t Pay Rent

A story about ego, fantasy, and the real cost of imaginary success

A Day in the Life of Jack “The Bomb” WoodBern

It was late October in North Carolina—the damp, indecisive season when the state can’t decide between summer sweat and winter chill. Jack “The Bomb” WoodBern stared out from WeatherGate Apartments, complaining about the weather the same way he complained about everything else—especially when nothing was going his way.

He sipped his coffee and stared at a blank Word document—his attempt at a masterpiece, an article that would outshine Woodward and Bernstein and finally give him the recognition he deserved, or at least desperately needed.

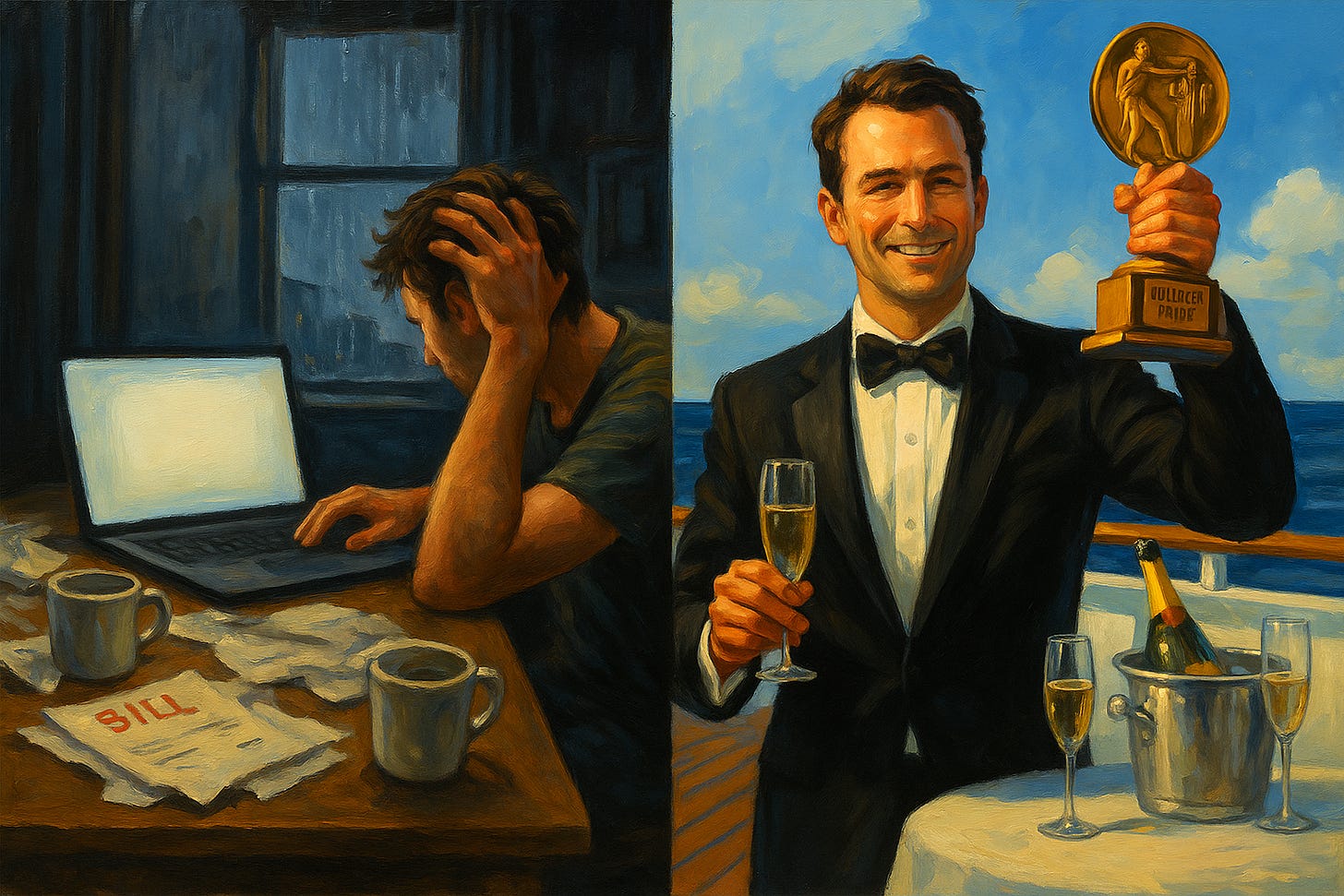

The blank page dissolved into fantasy. In his mind, Jack wrote the perfect article on the first draft, hit publish, heard the world cheer, and automatically received the Pulitzer. The Jury wouldn’t even wait for May; Columbia University’s president would personally fly down to North Carolina, knock on his apartment door, and hand him the prize. Fifteen grand in cash—finally enough to pay those overdue credit-card bills. Magazine offers would pour in. The world would finally see his genius.

If only he knew.

Jack had even founded his own media empire—The Daily Bomb LLC—complete with a domain, a logo, and exactly one article: “How Egocentric Bloggers Sabotage Themselves.”

He hadn’t posted since. If irony paid rent, Jack would be rich.

But this new piece—The Third Party—was going to change everything. It was his magnum opus: a hard-hitting exposé about foreign operatives using social media to incite chaos, secretly bankrolled by shell companies tied to OrionMega Corp, a conglomerate owned by major U.S. news outlets. In his head, it was Pulitzer-plus-Netflix-deal material.

The daydream escalated: yachts, champagne, interviews, applause.

When the fantasy faded, his coffee was cold and the document still blank. He typed one line, deleted it, sighed, and decided he “needed a break.” The Pulitzer would have to wait. Again.

He shut the laptop and opened his console. Investigative journalism could wait—there were digital dragons to slay.

The Knock

Later that afternoon, Jack returned to the blank document. Within minutes the fantasy started again: the ceremony, the handshake, the envelope of cash. Then—a sharp knock.

For one ridiculous, dopamine-drunk second, he actually thought his dream had manifested. He rushed to the door, grinning.

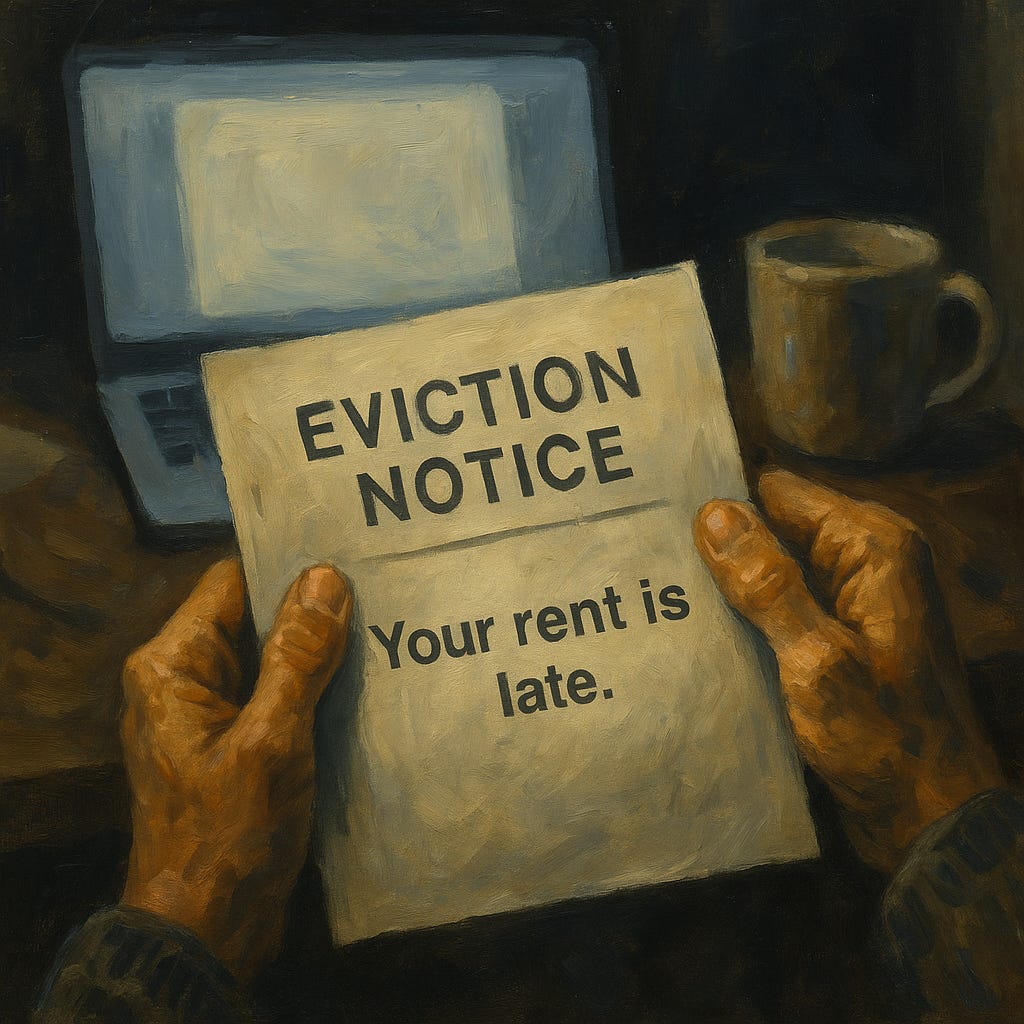

No one was there. Just an envelope.

He picked it up, still buzzing with leftover fantasy chemicals, and tore it open.

Hey Asshole,

Your rent is late. Pay me today or I file for eviction.

Jack stood in the doorway, note in one hand, empty mug in the other.

Behind him, the laptop sat on the table, the Word document still blank, still mocking him

.

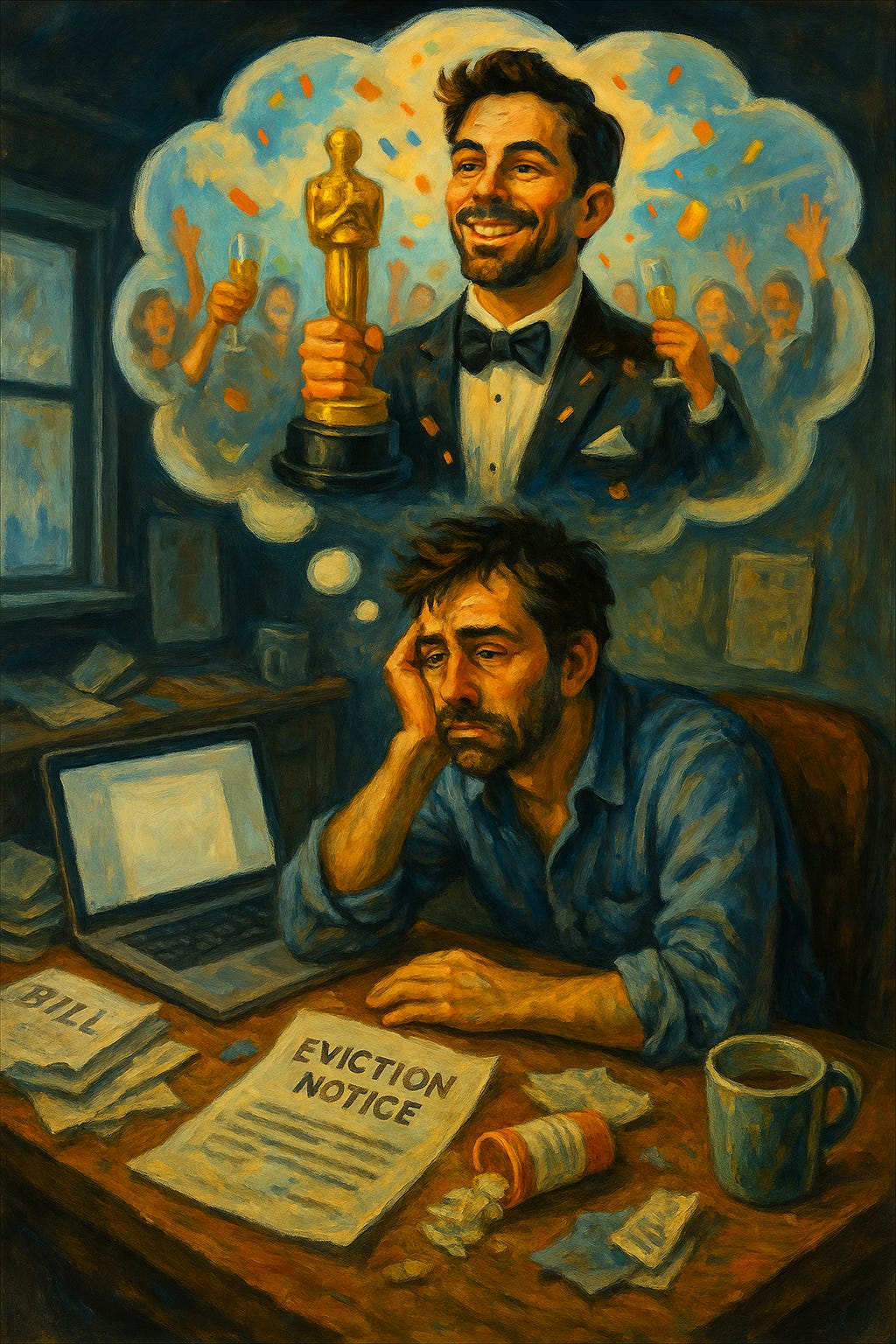

The yacht evaporated. The $15 000 dissolved. The Columbia president flew back to New York without ever leaving.

He closed the door, sat down, and stared at the blinking cursor. A year’s worth of unwritten articles, unpaid bills, and unfulfilled potential pressed down on him.

He needed to write. He needed to fix this.

Instead, he opened his game console.

Jack killed many more internet dragons that day.

Not a single sentence was written.

The Pattern

He didn’t know it yet, but he was trapped in a cycle psychologists have charted and philosophers warned about:

Fantasy → Dopamine → Satiation → No Action → Shame → More Fantasy

It feels like safety but works like quicksand—the more you indulge, the deeper you sink.

Jack thought he was lazy. Undisciplined. Maybe not cut out to be a writer.

He was wrong about all of it.

The problem wasn’t his work ethic, talent, or even his ego exactly.

It was something subtler, more insidious—and, thankfully, fixable.

Full Disclosure

Jack isn’t a character.

Jack is me—sort of.

I’ve spent more hours fantasizing about my media empire than building it. No, there’s no eviction notice on my desk, but I’ve been close enough to feel the draft.

Here’s what I’ve learned since Jack’s—since my—worst days:

there’s real neuroscience behind why this happens, ancient philosophy that diagnosed it two thousand years ago, and specific techniques that break the cycle.

In Part 2, I’ll show you:

The neuroscience of why ego-driven visualization kills motivation instead of fueling it

What the Stoics knew about the difference between productive imagination and destructive fantasy

Concrete practices that rewire the pattern—mental contrasting, process focus, and immediate micro-action

Because if you recognize yourself in this story, you’re not lazy.

You’re not undisciplined.

You’re not broken.

You’re just fantasizing wrong.

And that, at least, can be fixed.